Why are stress levels in corporate practices so high?

The sharp rise in the number of corporate practices is no secret. While most veterinarians work in independent and privately owned practices, corporatisation continues to grow.

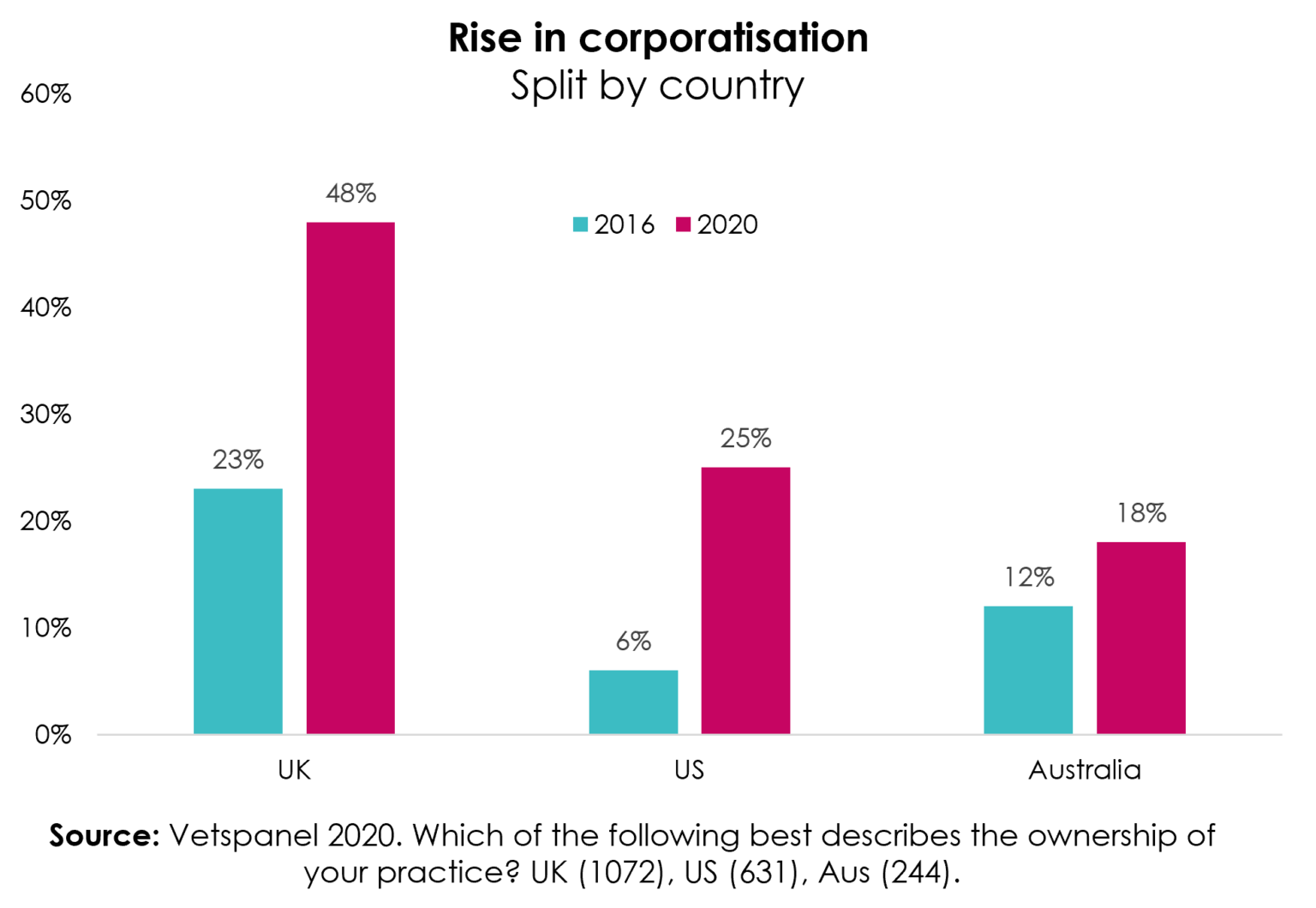

Data from our 2020 VetsSurvey identified that in the last five years, the number of corporate practices in the UK has more than doubled to 48%, nearly making up half of all practices.

In fact, more than half of veterinarians surveyed (56%) said they believed the number of corporate practices will rise even more in the next 10 years.

This trend is not solely rooted to the UK either, with the US seeing a significant rise from 6% in 2016 to a quarter of all practices (25%) in 2020, and Australia rising from 12% to 18% in that time.

UK, US & Australia see increased corporate ownership between 2016 & 2020.

With an increasing dominance in the industry, corporate practices have become reflective of the current struggles that are slicing through the industry at this current time, such as increased stress levels among veterinarians.

Data from a recent Vetspanel survey has found that stress levels in corporate practices are higher than those in independents.

One reason for this, may be that corporate practices naturally have more head office targets, and a drive to do more with less staff, piling more pressure on those in practices. Ultimately, decision making is detached from those who work day-to-day in corporate practices.

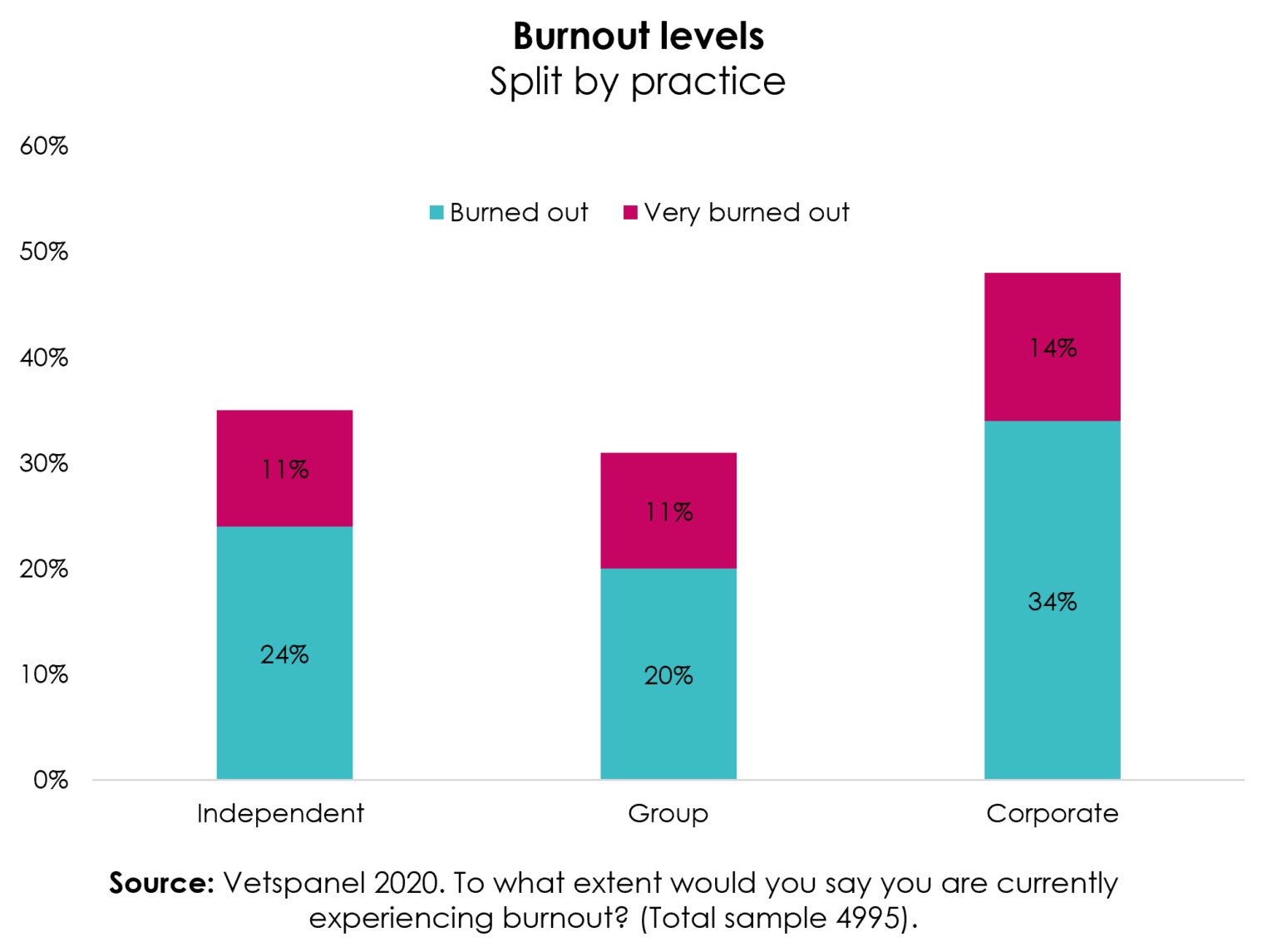

To worsen these issues, 48% of corporate veterinarians, more than independent (35%) and group practice (31%) veterinarians, reported feeling burned out.

Further data from our 2020 VetsSurvey found that corporate practices have a higher proportion of less experienced vets than group and independent practices. They also have a younger median age (38) than the average across the industry (43).

More burnout seen in corporate practices.

The appeal of corporate practices to younger vets can be attributed to the way that they are managed.

Independent practices can seem more attractive to older veterinarians as they naturally stay longer working for them and most provide the option for employees who work in them to buy into the practice.

Younger vets in corporate are working the longest hours which can lead to stress. However, corporates can provide monetary incentives which is a bonus for many of the newly qualified vets entering the industry.

One vet nurse we spoke with shared the sentiment of the appeal of increased earnings that come with corporates and that they “always pay more than independent practices,” but also added that “graduate schemes” are very popular for newly qualified vets.

The nurse added that many corporates are run with little staff, so the newly qualified vets are given almost too much responsibility very quickly.

“A lot of the corporates will put in a new grad, in a branch with their version of a qualified nurse [even if they only] just qualified, and their head nurse, a receptionist,” the vet nurse added.

So, how can corporates, which have higher numbers of less experienced vets; combat rising stress levels and an increasing need for more vets to be recruited before it’s too late?

More pastoral wellbeing support, something that should be prioritised across all practices, is a must for veterinarians. Compassion fatigue is at an all time high within the industry, and paired with the long-term challenges left by covid, employed vets should be prioritised.

As the number of veterinary professionals reporting increased stress levels continues to rise, it is hard to pinpoint one way to solve the crisis, but it is now more important than ever that corporate, as well as independent and privately owned practices start to address this epidemic, before it is too late.